Rebuilding Economies After Natural Disasters: What Does The Data Say?

As the climate crisis accelerates, natural disasters are becoming more frequent, more severe, and more economically disruptive. Europe has seen a sharp rise in extreme weather events, from catastrophic floods to uncontrollable wildfires, raising urgent questions about the resilience of national economies and the effectiveness of post-disaster recovery efforts.

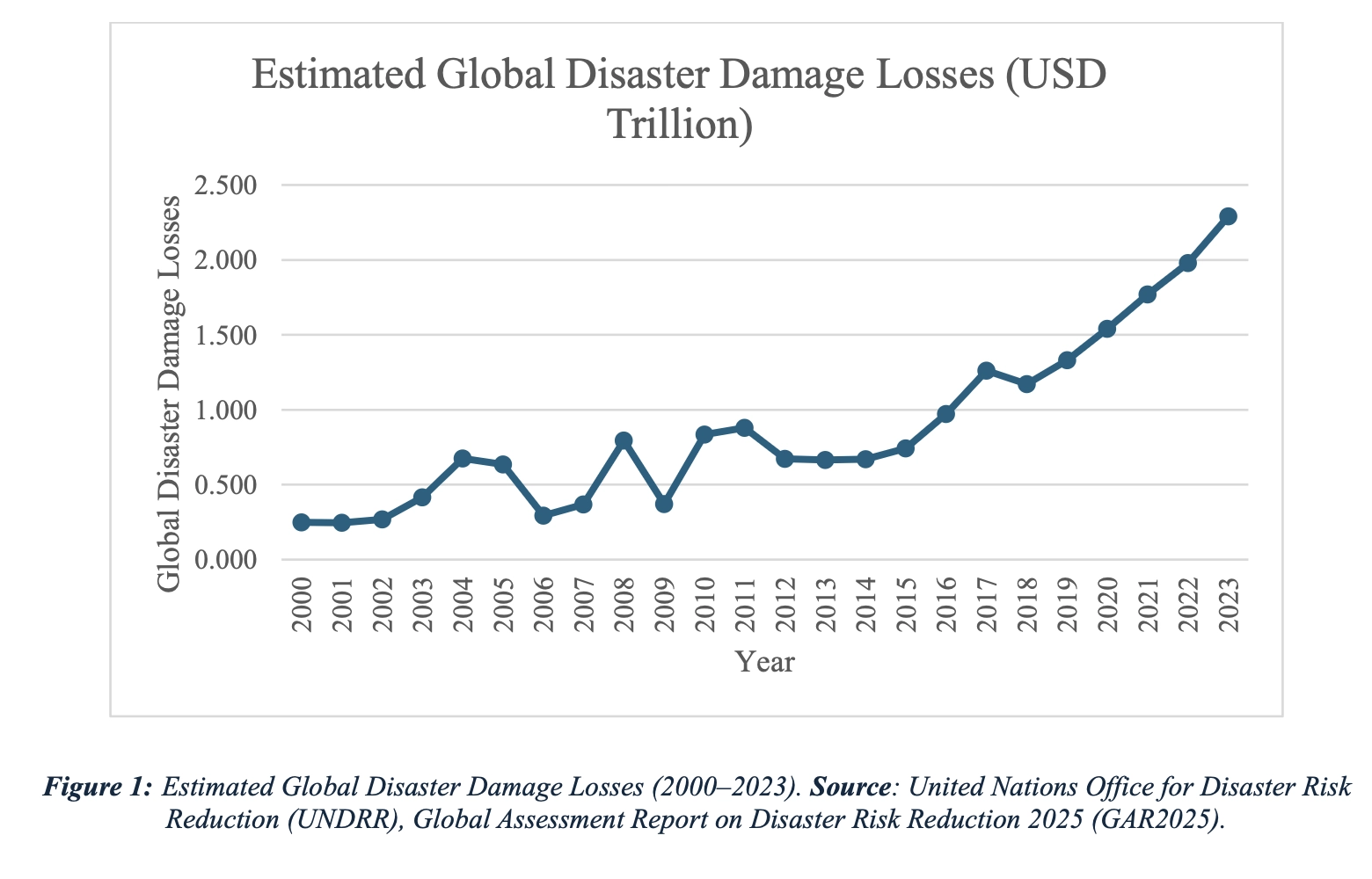

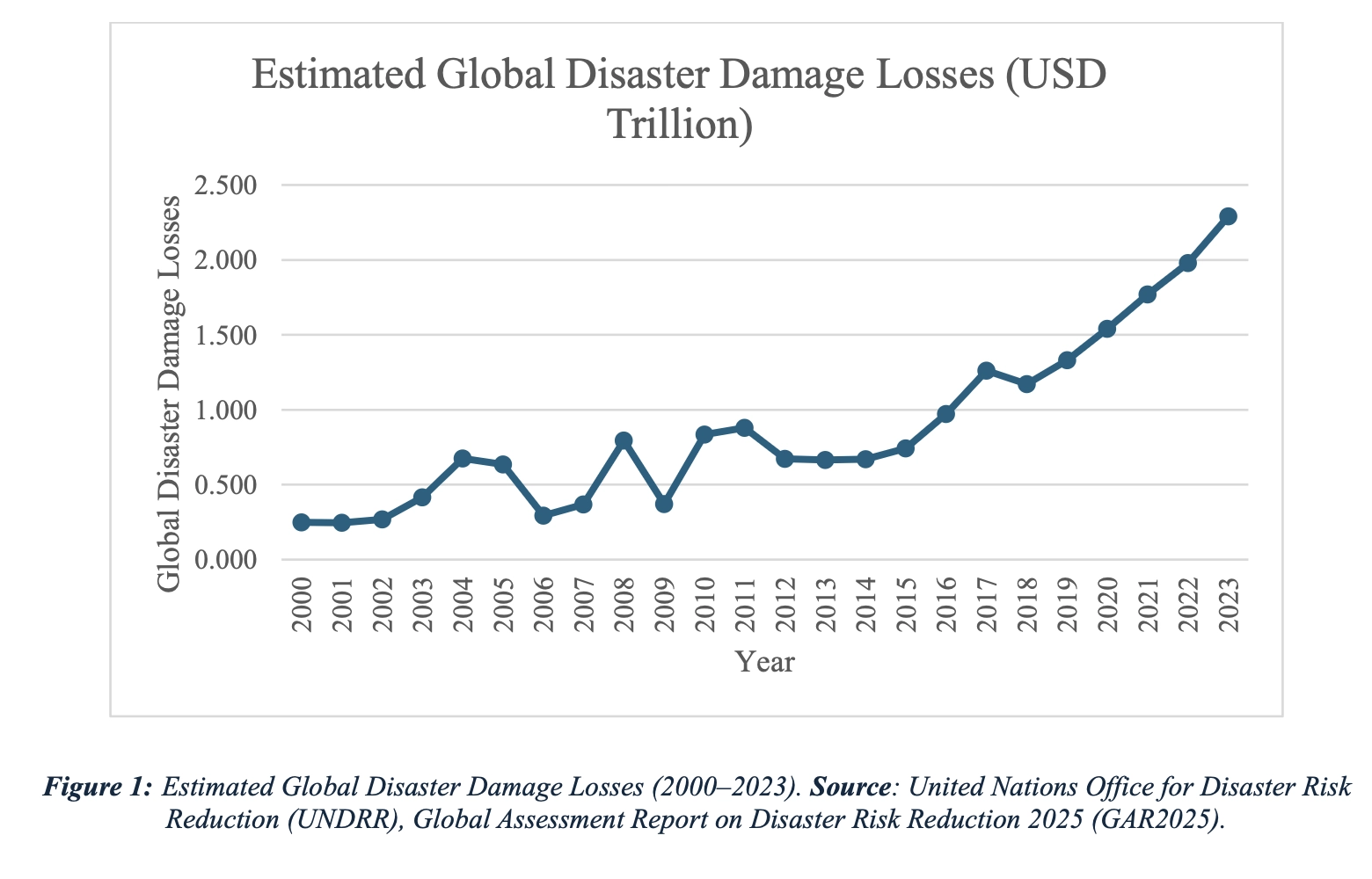

Nevertheless, the full financial toll of these disasters is often vastly underestimated. According to the Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction (GAR, 2025), while direct losses now exceed $202 billion annually, the true cost, including cascading effects, ecosystem degradation, and long-term social impacts, could exceed $2.3 trillion (Figure 1). To put this into perspective, a national debt of just $300 billion was enough to trigger the European sovereign debt crisis. Disaster risk is no longer a localised issue; it is now a systemic threat to global financial stability. The urgency of action is echoed by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, who stated:

These rising costs disproportionately affect developing economies, where weaker infrastructure, limited fiscal capacity, and external debt dependencies amplify post-disaster vulnerabilities. But recovery is not uniform: some countries rebuild quickly, while others face long-term stagnation or further deterioration.

Contents

- What does the literature say

- Which countries are most vulnerable and why

- The role of governance, social safety nets, and disaster preparedness in shaping outcomes

- And how Stata can be used to track post-disaster indicators, analyse recovery trajectories, and inform policy design through robust data visualisation and econometric modelling

Measuring the Economic Impact of Climate Disasters: What Does the Literature Say?

Despite a growing body of research, there remains limited consensus on how natural disasters affect local economies over time. The short- and long-run impacts can vary significantly depending on the region, the nature of the disaster, and pre-existing vulnerabilities. Recent work by Roth Tran and Wilson (2023) highlights that disasters act as negative shocks to both public and private capital, as well as to household wealth. This can lead to immediate business closures, investment withdrawals, and population displacement, driving declines in local income and productivity.

However, the theoretical literature offers more nuanced perspectives:

• Growth models such as the Solow model suggest that a one-time capital loss could trigger higher investment and output growth during the recovery phase, as the economy rebuilds toward its steady state. Likewise, neoclassical labour models predict that wealth losses may increase labour supply, potentially boosting employment and income in the short to medium run.

• Spatial equilibrium models, like those developed by Rosen (1979) and Roback (1982), emphasize how disasters affect local productivity and amenities, influencing migration, employment, and housing markets. For instance, a natural disaster may reduce local amenities, prompting outward migration and lower house prices. Alternatively, if rebuilding improves infrastructure, it could increase productivity and attract workers and firms.

A key insight from this literature is that housing and labour supply elasticities shape how regions absorb disaster shocks:

• In areas with inelastic housing supply, disasters are more likely to raise house prices due to limited rebuild capacity.

• In areas with elastic housing supply, disasters are more likely to reduce population as people move away.

These hypotheses have been empirically tested by Roth Tran et al. (2023), who find strong support for these theoretical predictions. Ultimately, this body of research reminds us that the economic trajectory following a disaster is not uniform, it depends heavily on local economic structures, institutional capacity, and the nature of recovery efforts.

Which Countries are the Most Effected: Size Matters

A growing body of literature underscores the powerful interplay between climate change, poverty, inequality, and social vulnerability. Smaller and lower-income nations, particularly those with limited infrastructure, weak institutions, and high dependence on climate-sensitive sectors like agriculture, are disproportionately affected. Climate-induced shocks such as droughts, floods, and heatwaves exacerbate existing resource scarcities, heightening the risk of conflict and forced displacement.

These pressures do not act in isolation. Climate change often amplifies long-standing structural inequalities, disproportionately impacting marginalised communities, ethnic minorities, women, and the poorest households. The competition for land, water, and food in fragile settings intensifies social tensions, while weakened governance further undermines resilience.

As a result, the demand for humanitarian aid and climate adaptation funding has surged, yet the ability of vulnerable countries to recover independently has diminished. Without coordinated global support and long-term investment in resilience, millions remain trapped in cycles of poverty and displacement, unable to secure stable livelihoods in the face of increasingly frequent disasters.

Countries Most at Risk from Climate Change

According to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN)1, some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries are also among the poorest and least equipped to manage the effects of rising global temperatures. At the top of the risk ranking is the Central African Republic (CAR), a country facing severe institutional fragility, limited infrastructure, and virtually no capacity to withstand or recover from climate shocks.

Eritrea follows closely, already experiencing a 1.7°C rise in average temperature, which has severely impacted agricultural output, an essential component of its economy. Other countries high on the climate risk index include the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, which has endured four consecutive years of devastating floods leading to a deepening hunger crisis, Guinea-Bissau, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Madagascar, all of which face recurring natural hazards like cyclones, droughts, and floods.

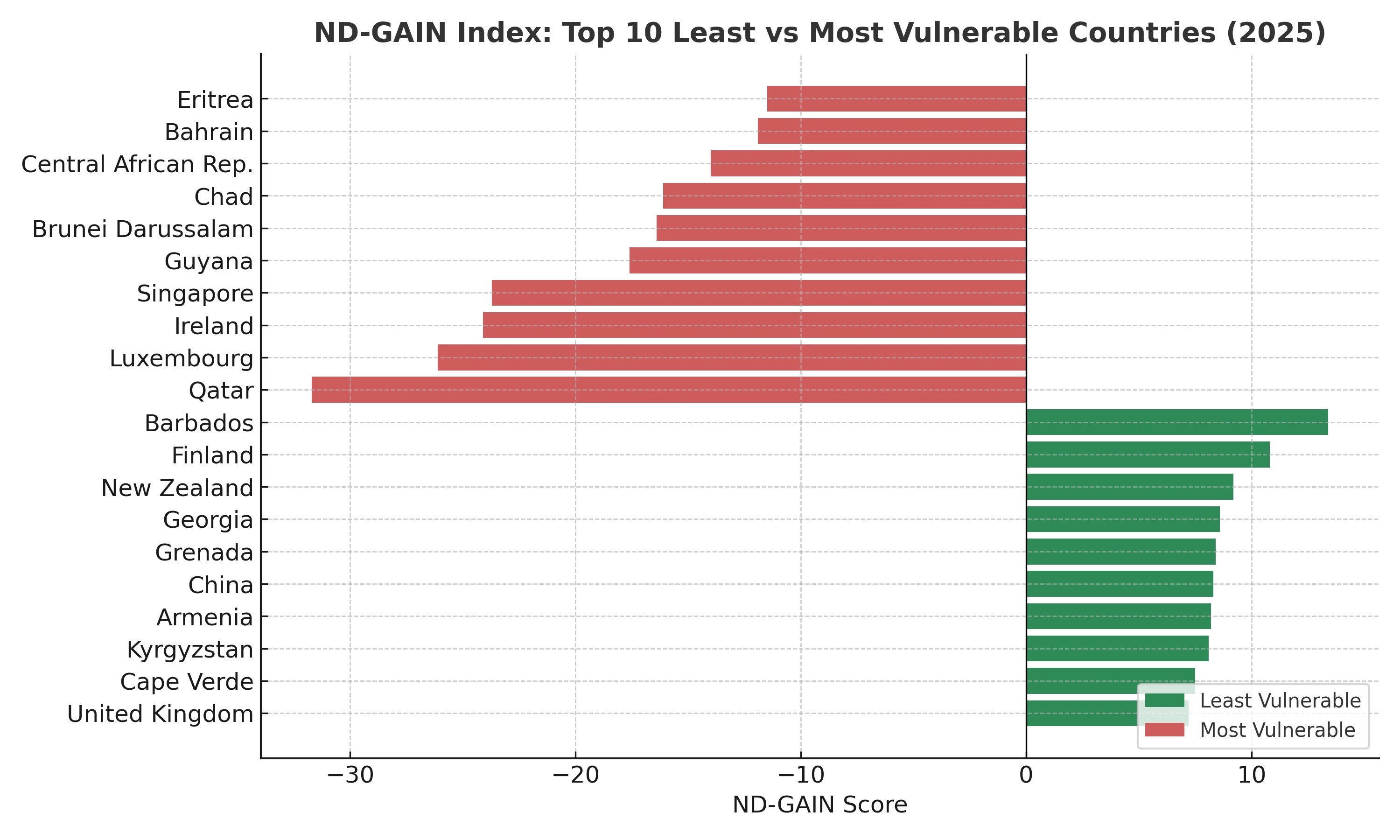

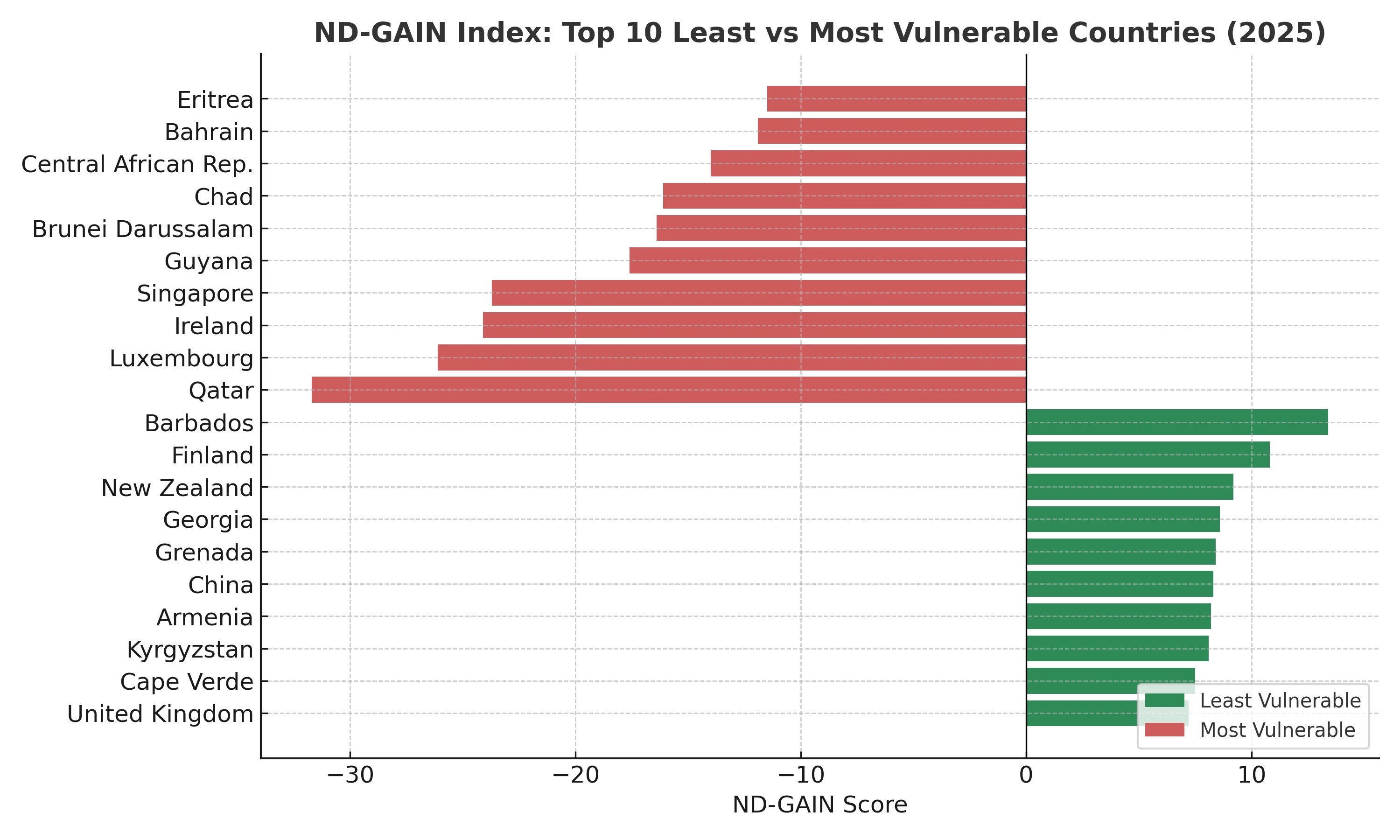

To better understand the interplay between climate vulnerability and economic development, the figure below plots the GDP-adjusted ND-GAIN Country Index2 comparing the top 10 countries with the highest and lowest resilience to climate change impacts. This index evaluates countries based on how their climate vulnerability and adaptive readiness compare to what would be expected at their level of GDP per capita. On one end of the spectrum, countries like Eritrea, Bahrain, and the Central African Republic show the lowest adjusted ND-GAIN scores, indicating extreme vulnerability due to low adaptive capacity and high exposure to climate-related shocks. These nations typically suffer from limited infrastructure, constrained public resources, and unstable governance, which severely hampers their resilience efforts. In contrast, countries such as Finland, New Zealand, and Georgia emerge as the most resilient, with positive adjusted scores reflecting strong institutional readiness, robust infrastructure, and effective climate adaptation strategies. Interestingly, the United Kingdom also appears among the top-ranked nations in resilience, underlining its institutional and economic capacity to manage climate risks. This divergence underscores the urgent need for targeted global support to enhance resilience where it is most lacking, especially in developing and fragile states.

1 The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index ranks countries based on their vulnerability to climate change and their readiness to leverage investments for climate adaptation. It provides a comprehensive measure of a nation’s exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, along with its institutional, economic, and social ability to respond effectively to climate-related challenges.

2 The “GDP-adjusted ND-GAIN score” represents the deviation of a country's actual climate resilience from its predicted resilience (based on GDP per capita). A positive score indicates a country is more resilient than expected, given its income level, suggesting strong governance or adaptive strategies. Conversely, a negative score highlights a nation more vulnerable than its GDP alone would suggest. By recalculating these deviations annually, the index captures shifts in resilience and readiness over time, offering a dynamic view of global climate adaptation disparities.

Figure 2: ND-GAIN Index – Top 10 Least and Most Vulnerable Countries (2025). Source: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), 2025 Country Index Rankings.

The Systemic Nature of Disaster Vulnerability: A Convergence of Global Crises

As we navigate through the compounding effects of climate change and natural disasters, it becomes increasingly clear that these events do not occur in isolation. Rather, they are deeply embedded in a broader tapestry of global instability. The current decade has brought to the forefront a complex web of interconnected systemic risks that magnify the socioeconomic and environmental consequences of disasters.

At the heart of this crisis lies a geopolitical landscape marked by fragmentation. Rising nationalism, geopolitical tensions, and the erosion of multilateral cooperation have weakened the global response to climate-related threats. Fragile states, already burdened by institutional collapse and conflict, face additional barriers to disaster preparedness and recovery.

Simultaneously, the world is confronting mounting economic fragility. Growing inequalities, high levels of public and private debt, and the volatility of global markets leave many economies ill-preparedfor the fiscal shocks that disasters impose. These conditions often lead to vicious cycles of poverty and vulnerability, particularly in low-income countries with limited adaptive capacity.

Technological advances, while offering solutions, have also introduced new risks. The rapid automation of industries and unequal access to digital infrastructure can deepen labour market disparities and reduce community resilience in the face of environmental disruption.

Meanwhile, the accelerating pace of environmental degradation, including biodiversity loss, deforestation, and the collapse of ecosystems, has heightened the frequency and severity of natural hazards. These environmental pressures are not only symptoms but also drivers of systemic instability, increasing the likelihood of cascading crises.

Finally, social fragmentation, driven by mental health crises, displacement, and declining trust in public institutions, erodes the social cohesion necessary for collective action. In times of disaster, these divisions exacerbate the breakdown of emergency responses and deepen community trauma.

Together, these five forces: geopolitical instability, economic fragility, technological disruption, environmental degradation, and social fragmentation; form the backbone of today’s disaster landscape.

Understanding and addressing these interlinked challenges is essential for crafting effective, equitable, and resilient recovery strategies. As emphasized in the GAR 2025 report, the systemic nature of disaster risk calls for integrated and forward-looking policy responses that go beyond short-term recovery and lay the foundation for long-term sustainability.

Policy Implications: From Committed Damages to Stategic Action

Recent research underscores a sobering reality: the world is already economically committed to significant climate-related damages through 2049, regardless of future emissions pathways. A study by Kotz, Levermann, and Wenz (2024) highlights that these damages, driven by past emissions and inertia in the climate system, are not only unavoidable but already outweigh the costs required to mitigate emissions in line with the Paris Agreement’s 2°C target.

This finding reframes the urgency of climate action. Traditional cost-benefit analyses have suggested that the net economic gains of climate mitigation would only become visible in the second half of the century. However, the magnitude of committed economic losses, already surpassing the costs of mitigation, makes a compelling case for frontloading investment in both mitigation and adaptation, even before the long-term savings materialize.

Crucially, adaptation offers a way to reduce the impact of these already-locked-in damages. This includes strengthening infrastructure, building early warning systems, improving land use planning, and enhancing health and education systems in vulnerable regions. Yet, despite the proven returns on investment in resilience, often yielding benefits that far exceed initial costs, both private and public adaptation financing remain woefully inadequate, especially in low-income and climate-exposed countries.

This gap is not merely a matter of delayed investment; it reflects a deeper market and governance failure. International financial institutions, national governments, and development agencies must rethink their priorities to ensure that resilience building, and disaster risk reduction are central to economic planning. Doing so not only safeguards future prosperity but also provides immediate economic stimulus and employment opportunities.

Ultimately, the data point to a simple but powerful conclusion: the cost of inaction is far greater than the price of preparedness. By acting now, before climate impacts escalate further, policymakers can transform looming risks into opportunities for more sustainable, equitable, and resilient growth.

Conclusion

As climate change intensifies, so too does the frequency, severity, and cost of natural disasters, pushing already vulnerable economies closer to crisis. From the disproportionate impact on low-income countries to the economic damages the world is already committed to through mid-century, the message is clear: inaction is not an option. Disaster risk is no longer a peripheral development issue; it is a systemic threat to global economic and social stability.

This blog has explored how disasters interact with broader forces like inequality, migration, weak institutions, and fragile ecosystems, and how recovery trajectories vary widely between countries. We have seen that resilience is not just about infrastructure, it’s about governance, social protection, and strategic investment in preparedness. Moreover, the economic case for adaptation and mitigation is no longer theoretical: it’s measurable, immediate, and increasingly unavoidable.

But turning this understanding into effective policy and planning requires more than urgency, it requires data, precision, and the right analytical tools. Stata offers a robust and flexible environment to support each stage of disaster risk and resilience research, including data collection, data cleaning, descriptive analytics, and visualisation. If we are to prepare effectively for a future shaped by climate extremes, we must invest not only in infrastructure, but in information. Stata helps turn that information into insight, and insight into impact.

Francisca Carvalho, Lancaster University

Francisca is a third-year PhD student in Economics at Lancaster University. Her research focuses on climate risk factors and their impact on portfolio returns. She also teaches mathematics, econometrics, macroeconomics and microeconomics, to undergraduate and postgraduate students.

GAR (Global Assessment Report). (2025). Resilience Pays: Financing and Investing for Our Future. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Retrieved from https://www.undrr.org/gar/gar2025

• Hsiang, S. M., & Jina, A. S. (2014). The causal effect of environmental catastrophe on long-run economic growth: Evidence from 6,700 cyclones. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 20352. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20352

• Kotz, M., Levermann, A., & Wenz, L. (2024). The economic commitment of climate change. Nature, 628, 551–557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0

• Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). (2025). ND-GAIN Country Index. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved from https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/

• Roth Tran, B., & Wilson, D. J. (2023). The local economic impact of natural disasters. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2020-34. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2020-34

• Roback, J. (1982). Wages, rents, and the quality of life. Journal of Political Economy, 90(6), 1257-1278.

• Rosen, S. (1979). Wage-based indexes of urban quality of life. Current issues in urban economics, 74-104.

• UNDRR. (2025). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2025: Resilience Pays. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.undrr.org

• United Nations Secretary-General. (2025). Statement on the Global Assessment Report 2025. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.